Last Saturday was one of those days that divides time into a before and an after. After sixty uneventful years, our airport experienced its first fatal accident. A landing aircraft, for reasons unknown, veered off the runway and crashed into a section of woods between two homes, killing one person on board and severely injuring two others. Being at the other end of the field, I didn’t know about it until several hours later.

Mercifully, I wasn’t one of the first on the scene, and don’t have images of explosions and burned passengers imprinted in my memory. In fact, I had no real desire to visit the crash site; I didn’t look closely until several days later, after the NTSB had been and gone. Beyond the charred trees though, there wasn’t much visible – when a fiberglass airplane burns, little remains.

The field reopened the next day, and as I had plans for a trip, I could see no reason not to launch. No logical reason, that is.

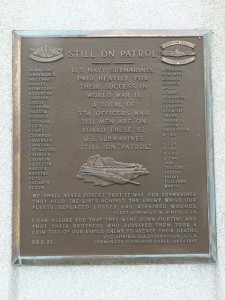

We all process our mortality in our own way. Most of the time, death happens offstage, out of the way, where we don’t have to deal with it directly. We’re not supposed to have our noses rubbed in it on a beautiful summer morning, amid blue skies and a pleasant breeze.

Our airfield is slightly less than half a mile long, and on takeoff there’s a fleeting moment when you start thinking that faith does play an element in this. Tach and manifold pressure normal, ground speed increasing, past 50 knots and I need 68 before I can fly… those trees are coming up awfully fast. Ease back on the yoke and we leave the ground; wheels up so we can climb as quickly as possible, and clear the trees by as much as possible. The airplane’s performance is documented and predictable – a table in the operating handbook tells what distance is needed to leave the ground, and to clear a fifty-foot obstacle. The engine and the rest of the plane are meticulously maintained, the fuel is proper and uncontaminated by water, and there’s nothing challenging about today’s weather. So why do I feel like I’ve cheated death?

Level at cruise altitude, autopilot on, new age music on the player, and some time to pause and reflect. Perhaps it would simplify things to remove this risk factor from my life. There would be financial benefits, too. I notice a small, lone sailboat somewhere off the coast of Newport, and I wonder if it’s pilot is having similar thoughts.

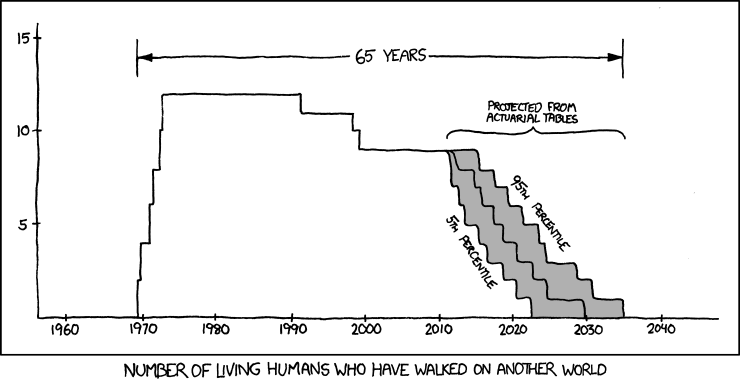

Most likely, I’ll be dead fifty years from now. I can run my life in a manner that will stretch that time for as long as possible, but the years would be unbearably empty. No bicycling. No pastry. No flying. And a bunch more nos that I can’t even think of right now.

All told, I think I’d rather spend the time Living, even at the risk of shortening it some. I push the disengage button on the autopilot and fly it by hand for a while. After all, that’s why I’m here.